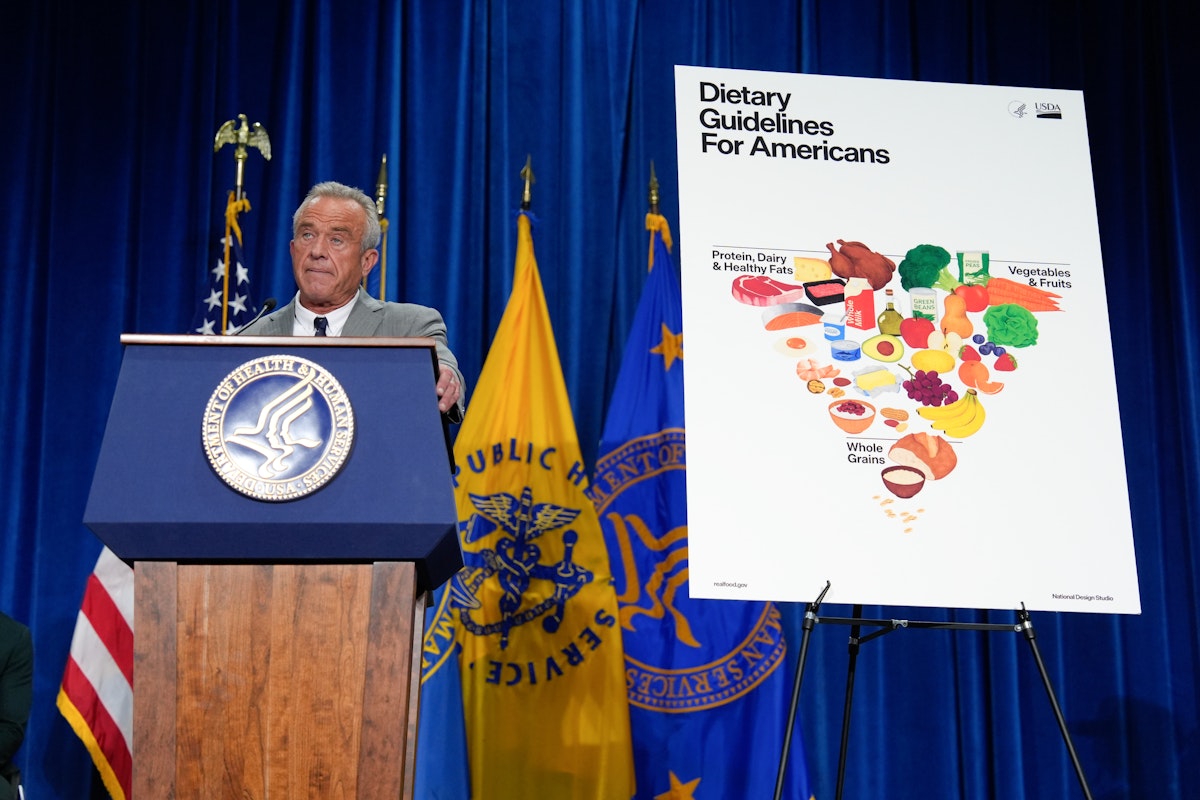

The United States Department of Agriculture’s new-look food pyramid, released last week to accompany a new set of Dietary Guidelines for Americans, looks more like a minimalist poster designed to be hung in a foodie’s kitchen than a piece of government policy. Underneath the invitation to “Eat Real Food,” the inverted pyramid is made up of drawings of diverse foods grouped into three categories: protein, dairy, and healthy fats; vegetables and fruits; and whole grains. On its surface, innocuous. But a closer look reveals a piece of ideological art designed to upset the consensus on healthy eating and, perhaps, own the libs. The eye goes first to the fat cut of steak, then the wedge of cheese, a whole roast turkey, a package of ground beef, a carton of whole milk, then a bounty of fruits and vegetables that brings one down to an unwrapped stick of butter, and finally, at the bottom, brown and unappealing, a loaf of sourdough bread and a bowl of oatmeal. Given previous guidelines’ slow drift away from meaty and cheesy diets in line with expert consensus, these guidelines are less of a public health intervention and more of a meme: a message to the political and cultural constituencies like the MAHA moms and the carnivorous corners of the manosphere.

The USDA has been releasing dietary guidelines since 1894 and visually representing them for the public since 1943. It began with a color-coded circle made up of the “Basic 7” food groups, urging Americans to eat from each one every day. This was replaced in 1955 with a “daily food guide” made up of the four food groups that remain etched into contemporary nutrition discourse: milk, meat, fruits and vegetables, and bread and cereals. In 1977, the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs (commonly known as the McGovern Committee) recommended that Americans eat less refined sugar, red and fatty meat, dairy, and eggs, and more fruit and vegetables. In 1992, the “food pyramid” was introduced, schematizing five food groups—fruits and veggies were separated, beans and nuts added to meats to make a de facto “protein” category—as an ascending structure that should guide daily food consumption, accompanied by the introduction of daily recommended servings of each food group. This, in turn, was replaced in 2011 by MyPlate, a much-discussed reset that laid out the five food groups in proportional quantities on a plate as a heuristic for crafting healthy meals. Now, the Trump administration has re-introduced the food pyramid, but turned it upside down—perhaps a little too on the nose.

The dietary guidelines have always had two purposes: first, to be an educational tool and prompt for the American public to eat more healthful diets, and second, to serve as the basis for dietary and food procurement policy for institutions like schools and the military. They’re a product of a tense interplay between politics and science. Although based, since 1985, on reports prepared by committees of nutrition experts drawn from government and academia, seeking to distill the latest peer-reviewed literature, the recommendations have also reflected committee members’ own prejudices, as well as pressure from the food industry, which funds many academic nutrition researchers and has long lobbied over public-facing dietary advice (the meat industry, for instance, has opposed any overt criticism of meat or promotion of plant-based protein in the guidelines).

But the guidelines have been slowly moving toward representing a growing scientific consensus about healthy diets, championing a range of proteins and fortified foods as well as whole and fresh foods, and tailoring recommended serving sizes to consumers’ caloric and other health needs. Instead of showing any particular foods as visual cues, the MyPlate image simply showed proportions of food groups on a plate, leaving the contents up to consumers’ cultural and gustatory preferences as well as budgets.

The problem is that Americans don’t generally heed the government’s advice. While scholars of nutrition might balk at this simplification, all federal food guidelines have urged Americans to eat balanced, moderated diets made up of a variety of foods. It just hasn’t worked. Today, about 40 percent of adults in the United States are obese, 36.4 million people have type II diabetes, and almost 100 million adults are pre-diabetic. On a metric called the Healthy Eating Index that compares American diets to the recommendations (with a score above 80 out of a 100 denoting healthy eating), the mean score for Americans is a 57. The reasons for this are varied. They range from culturally entrenched dietary habits to food environments swamped with unhealthful choices. (It bears noting that the price of food is actually not a key determinant of healthier eating—the richest Americans still score poorly on the HEI.) The biggest shortfalls are on fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, just as they were in 1977 when the McGovern Committee released its report. Meanwhile, Americans consistently eat sufficient protein.

While, overall, Americans’ diets remain wretched, the dietary guidelines and MyPlate have been provably effective in shaping school lunches; despite their bad reputation, these school lunches have been found by research to be among the healthiest meals the average student eats during the day. But that’s because lunches covered by the USDA are de facto mandated; individual consumer choice is not.

So if the guidelines aren’t the problem, why change them? The answer may lie less in careful public health analysis than in the priors of those shaping them and the constituencies who support them. To the extent the new guidelines differ materially from those that preceded them, it is primarily around the promotion of far higher amounts of protein (almost double what was previously recommended), explicit opposition to most processed foods, and a more permissive approach to alcohol. For those on the right, the new guidelines confirm what many people want to believe about the diets they already have: eat steak, no matter what the liberals say. For the broader MAHA movement, the imperative to “eat real food” rings of common sense. (“Eat real food” was famously a core recommendation of the liberal journalist Michael Pollan-and signals opposition to agribusiness and food technology—although Pollan followed that with a crucial caveat: “mostly plants.”)

The MAHA right’s target here isn’t just liberals, though; it’s the public’s general faith in bureaucratic processes, expertise, and science. Despite the administration’s claims that the new guidelines would fight against agribusiness special interests, they have done no such thing. The government mostly ignored the advice of its advisory committee in favor of a different, handpicked committee heavily linked to the meat and dairy industry. Rather than rejecting scientific expertise outright, the new guidelines are based on the findings of a select group of experts who happen to support the priors of members of the administration. In that sense, the guidelines and the new pyramid function as a culture war scalp, valued because they represent right-wing political ascendency: At long last, the American right may crow, they’ve brought previously aloof government agencies and academics to heel.

For liberals, the guidelines may now seem a synecdoche for the faltering trustworthiness of government expertise, particularly on questions related to health. As the MAHA movement has taken aim at medical issues where their beliefs are at odds with the consensus of most medical experts, most notably on vaccines, the effect of such symbolic victories could sour the public on state expertise writ large. Ironically, an openly corrupt process that produces a bizarre result on a notoriously sensitive issue would benefit the portions of the right that want to dismantle as much of the government as possible. Given the volatile and growing anxiety about the future of meat, in particular, these actions could inflame and polarize engaged citizens as well as sow distrust of the very agencies and institutions that are needed to contain corruption.

To the extent the guidelines—so similar yet so different, and crucially so differently branded from their predecessor—represent an agenda, it is not simply to facilitate a particular outcome favored by meat corporations but also to invert good governance liberalism. Proponents of an efficient regulatory and welfare state aim to deliver effective public services precisely to strengthen a broader case for the value of government itself. Conservatives have long sneered at this approach and argued government must be reduced; in his 1981 inaugural address, Ronald Reagan famously declared, “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

But as much enthusiasm as they had for reducing government, Reaganites rarely have made a public case for suborning it. MAHA’s institution-wrecking turns Reagan on his head much like it does the pyramid: the solution, it seems to suggest, to a citizenry grown overly dependent on the state is not less government, but contrarian government. Americans, of course, will probably ignore this guidance much as they have the last century or so of prior guidance, continuing to feast on meat and fat and reaping the long-term health rewards. The lasting legacy of the inverted pyramid, however, may well be kids fed artery-clogging meatloaf at school—with a side of declining faith in both government and science.

Hence then, the article about how the new food pyramid fits into the broader conservative project was published today ( ) and is available on The New Republic ( Middle East ) The editorial team at PressBee has edited and verified it, and it may have been modified, fully republished, or quoted. You can read and follow the updates of this news or article from its original source.

Read More Details

Finally We wish PressBee provided you with enough information of ( How the New Food Pyramid Fits Into the Broader Conservative Project )

Also on site :

- commercetools Kicks Off NRF 2026 - including Updates on Stripe ACS, AI Hub, and Helping Enterprises Stay Discoverable and Shoppable in Agentic Commerce

- inDrive turns to ads and groceries to diversify revenue

- Clover Initiates Phase 2 Clinical Trial for RSV + hMPV ± PIV3 Respiratory Combination Vaccine Candidates