Often attributed to Mark Twain — perhaps mistakenly, since no historical source shows he actually made the statement — “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes” is a common and apt refrain when discussing the connection between historical perspectives and current events. By drawing on knowledge of what happened in the past, and why, we are better able to understand the flow and direction of the history collectively created in each new day.

“Past Rhymes With Present Times” is a series by Lloyd S. Kramer exploring historical context and frameworks, and how the foundations of the past affect the building of the future.

Current government campaigns to deport immigrants, expel foreign students, defund scientific funding, and dismantle all programs for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) have become the most far-reaching crackdown on targeted populations and ideas in modern American history.

Native Americans and Japanese Americans were expelled from their homes in past centuries, and enslaved African Americans were frequently separated from their families before the Civil War, but most living Americans have never seen such aggressive immigrant arrests and deportations or such systematic efforts to demolish medical research and international diversity in renowned universities.

Pragmatic Nationalism and Ideologies of National Uniformity

The multiple assaults on people and institutions are violating well-established legal and cultural traditions, but they are also undermining America’s future economic development, health care, climatic conditions, and scientific creativity.

Economists have shown, for example, that undocumented immigrants account for about 14% of the nation’s workforce in the construction industry, 13% of America’s agricultural laborers, and over 7% (one million people) of the workers in the vast hospitality system.

Meanwhile, the essential work of scientific researchers, public-serving cultural institutions, and global-facing international students has stalled everywhere as billions of dollars disappear from distinguished universities, as museums and theaters lose government support, and as new obstacles block the visas or travel rights of talented foreign students and scholars.

These self-destructive public actions are unprecedented in the modern United States, but governments in non-democratic societies have long purged people whose identities, beliefs, or cultural traditions differed from the ideological fixations of the reigning regime. Economic needs and cultural creativity were less important in such places than obsessive beliefs that dissenting religious or political groups and even essential workers must be repressed or expelled to safeguard the nation’s social and cultural unity.

This endless quest to establish the imagined coherence of national communities connects America’s current deportations of undocumented workers with the systematic efforts to destroy global connections and DEI perspectives in our educational institutions. Foreign-born students and the advocates of multiculturalism are condemned like foreign-born workers for spreading a contagion of ideas, languages, and social practices that threaten the wider (but always unattainable) cultural unity of the American nation.

Although the search for illegal ideas differs from the search for illegal workers, those who now argue for more racial or multicultural diversity in universities or government agencies may lose their jobs almost as quickly as the undocumented workers who are grabbed and deported from American farms and streetcorners. This threat has already become a reality for some UNC-system employees who resigned from university positions after expressing support for DEI goals or ideas in secretly recorded conversations.

The UNC Board of Governors (BOG) has recently decided to ensure that all such ideas disappear from our state’s public universities by launching investigations into “realigned” staff positions and reorganized programs that might covertly advance the objectives of diversity, equity or inclusion.

As the BOG leaders explained in a June directive, the Board of Trustees at each UNC institution must create a five-member subcommittee to look for administrators, faculty, and staff who may be hiding diversity projects under a façade of renamed positions or programs that secretly promote now-banned DEI goals.

Although the BOG guidelines suggest innovative new strategies for assuring staff adherence to university-wide policies and ideas, this project of educational purification–like the broader national campaign to remove all “irregular” workers from the American economy– resembles long-existing patterns of cultural purges in other times and nations.

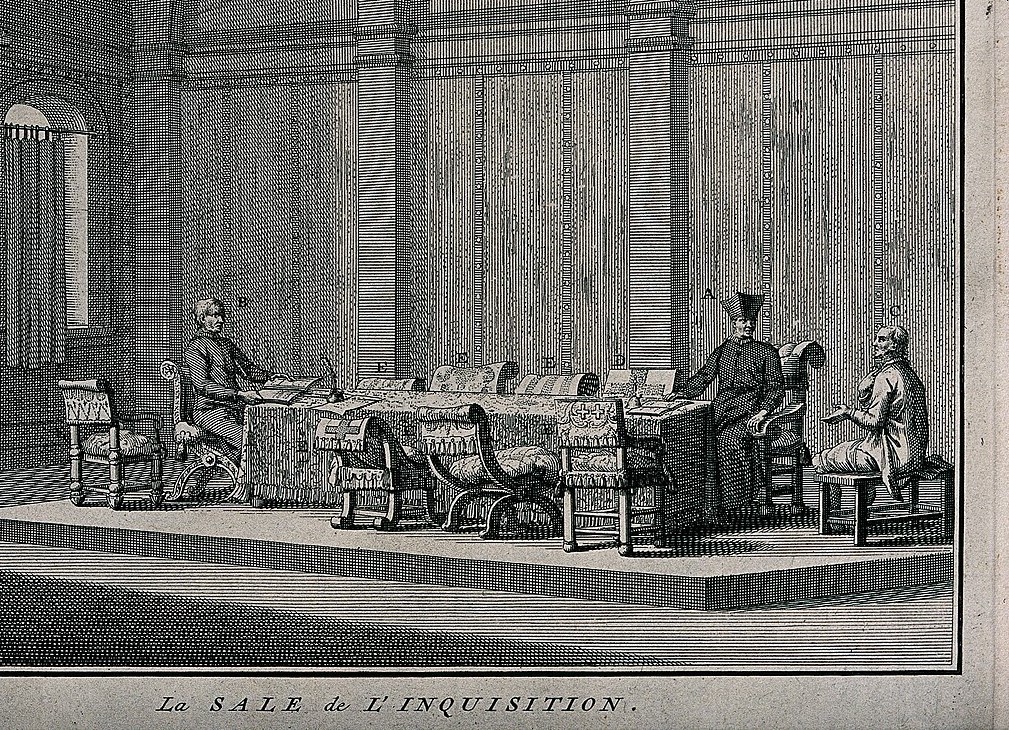

An interrogation room of the Spanish Inquisition with two priests and an accused heretic. Engraving by B. Picart, 1722

The History of Religious and Political Purifications

Campaigns to “root out” secret believers in dangerous ideas appeared often in the medieval Catholic church’s punishment of heretics, but the quest for purification later evolved among secular extremists in modern political upheavals. There were famous campaigns to purge secret Trotskyite heretics in the Soviet Union during the 1930s or to identify secret bourgeois bureaucrats in China’s Cultural Revolution during the 1960s or to unmask secret monarchists in the French Revolution during the 1790s.

In every revolutionary transition, newly empowered political leaders were certain that the contagion of a previous regime was still lurking in the minds and hidden actions of people who had somehow retained influence in the new system.

These famous political purges perfected and expanded the great religious repressions of the early modern era. One of the best-known purges developed in France after King Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, thereby denying Protestants (called Huguenots) all rights to practice their religion, proselytize their beliefs, or hold public offices.

The Huguenots’ earlier freedom to live, work, and worship in their own communities had fostered diverse commercial activities and valuable craftwork that enriched the whole French economy. The king’s obsessive desire to suppress religious diversity nevertheless overruled all financial concerns about expelling Protestant workers—whose departure reduced the skilled labor and trade in French cities while enhancing the commerce in every foreign nation to which they migrated. Hundreds of thousands of Huguenots fled France, but others converted to an always-suspect Catholicism that would be investigated and punished for almost a century.

The most famous early modern search for “fake conversions,” however, took place in the great Spanish Inquisition of the 16th and 17th centuries. Large Jewish and Muslim communities had long flourished in Spain, but royal decrees in 1492 and 1502 ordered all Jews and Muslims to convert to Catholicism or face the punishments of Inquisition tribunals.

Thousands of Jews and Muslims (like the Huguenots in France) abandoned their commercial enterprises and self-deported from Spain, but many remained in their hometowns and converted to Catholicism to protect their families or pursue their previous work. The Jewish converts were called “Conversos,” and the Muslim converts were called “Moriscos.”

Spanish kings and church leaders responded to these mandated conversions with fearful concerns that most Conversos and Moriscos still held their earlier beliefs and secretly practiced forbidden rituals. Inquisitorial tribunals were therefore assigned to investigate the distrusted communities and to find the “false converts” who threatened Spain’s unified national faith.

The Inquisitors worked hard and produced impressive results. Friends and neighbors were urged to look for insincere Conversos or Moriscos and provide evidence of false conversions to the investigating tribunals. These secret reports contributed to the prosecution of at least 150,000 Conversos and Moriscos who lost their jobs, their property, and their possible appointments to government or church positions. More than 3,000 people were even burned at the stake.

Fortunately, we are not living in a place where the exposure of false conversions will lead to public executions or the confiscation of houses. But the five-person BOT committees (which include no faculty or staff) will have the institutional power to find and remove the fake DEI Conversos who may still be working within our universities.

We don’t know if the committees will identify all the hidden Conversos, but such people surely exist, and there will be strong pressure for their contagion to be removed. When did self-certain committees of talented inquisitors ever fail to find the dreaded beliefs or activities they set out to discover?

The BOG’s mandatory investigations, like the national policies that seek to identify and remove undocumented immigrant workers, thus evoke memories of social or cultural purifications in other societies. Although each campaign tries to eradicate different contagions and imposes different punishments, the recurring patterns of suspicion, surveillance, investigating tribunals, and scapegoating are entirely familiar.

Conversos and the Fragility of Tolerance

It may seem strange to compare current expulsions and purges with historical precedents because the fears of past generations seem less rational or valid than the fears of our own time. We wonder why King Louis XIV’s government became so fearful of French Huguenots, as future generations will wonder why twenty-first-century Americans became so fearful of immigrant workers and the social goals of DEI.

Fears of difference are continually regenerated in the cultural anxieties that mobilize political movements and justify repressive policies in modern nations. We saw one American example during the 1950s when McCarthyism drove ex-communist Conversos out of universities and movie companies, but the search for false Conversos is again endangering both obscure and prominent people in 2025.

Such perils have recently reappeared (among many other places) at the University of Virginia, where President James E. Ryan was forced to resign because critics said he had failed to purge the institutional vestiges of DEI; and Ryan’s displacement replicates the earlier rejection of Santa Jeremy Ono’s nomination to become the president at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

Despite unanimous support from a UF search committee, wide-ranging leadership experience at the University of Michigan, and careful efforts to show that he had converted from his former belief in the goals of DEI, Ono lost his recommended appointment because Florida’s system-wide Board of Governors judged him to be a fake Converso who should never lead one of their state universities.

The search for fake Conversos and the threats of “disciplinary action” are now coming into North Carolina’s public universities. We know from history as well as our own experiences that tolerating people and ideas we fear or dislike has never been easy, yet the legal construction of such tolerance is one of liberal democracy’s greatest achievements.

When the traditions of political tolerance and cultural diversity collapse in a nation’s governing institutions, however, democracies evolve into autocracies, and dissidents suffer the punishments of state-sponsored Inquisitions.

Photo via Lindsay Metivier

Lloyd Kramer is a professor emeritus of History at UNC, Chapel Hill, who believes the humanities provide essential knowledge for both personal and public lives. His most recent book is titled “Traveling to Unknown Places: Nineteenth-Century Journeys Toward French and American Selfhood,” but his historical interest in cross-cultural exchanges also shaped earlier books such as “Nationalism In Europe and America: Politics, Cultures, and Identities Since 1775” and “Lafayette in Two Worlds: Public Cultures and Personal Identities in an Age of Revolutions.”

Past Rhymes With Present Times: Purges, Expulsions, Conversos, and DEI Chapelboro.com.

Read More Details

Finally We wish PressBee provided you with enough information of ( Past Rhymes With Present Times: Purges, Expulsions, Conversos, and DEI )

Also on site :

- Opinion: Tolerance of diversity is central to San Diego’s economic growth

- ‘Deeply concerned’ over India press censorship, says X as accounts blocked

- King Charles, 76, Draws Concern From Royal Watchers Amid Cancer Treatments